The next time you’re on a flight and the seat-belt sign clicks off, glance out the window. Six miles below, the landscape looks peaceful and small. Now picture a single rock—silent, ancient—so massive it could stretch from the ground up to that cruising altitude. That was the size of the asteroid that ended the dinosaurs’ reign.

That kind of disaster isn’t just ancient history. Every couple of weeks, something big enough to flash across the sky as a brilliant fireball—astronomers call it a “bolide”—slams into our atmosphere. Most flare and die harmlessly. A few make it to the ground. The odds are small, but the stakes are enormous.

That’s one reason I built the Wolf Moon Observatory. I’m not just watching the sky for beauty. I’m part of a quiet, worldwide vigil—an early-warning system for our restless solar system.

But when darkness falls and the clouds clear, I slide back the observatory’s steel-tracked roof. The sky above turns into a vast, star-strewn sea, and I feel that familiar tingle—the sense that tonight, a new story might begin, or a new threat might be spotted, glinting faintly against the drift of stars.

Mission 1: Astrometry — Playing I-Spy with the Cosmos

I often describe astrometry as the most high-stakes game of I Spy ever invented. I take a rapid series of images of the same star field, then compare them frame by frame, hunting for the faintest dot that doesn’t quite stay put. If a speck moves against the fixed stars, it’s a wanderer—an asteroid, sometimes a newly tracked one.

The techniques need precision. The universe doesn’t tolerate sloppy work. I don’t expect to out-discover the robotic survey telescopes that sweep the skies every night, but I can still join the hunt. And that, for me, is part of the thrill: the idea that a quiet backyard observatory can be part of a global early-warning network.

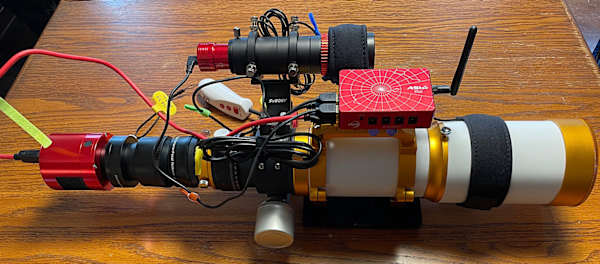

My gear isn’t exactly cutting-edge, but it has earned its scars. I still rely on the Celestron 11-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain I bought in 2001, now mounted on a rock-steady Losmandy G11G equatorial mount. I’ve tuned the optics from f/10 to f/6.3 for a wider field of view, paired it with a ZWO ASI533MC Pro camera and an 80 mm guide scope. Soon I’ll upgrade to the ASI2600MC Pro for even sharper tracking of faint, distant worlds—some drifting far beyond Pluto.

Every time I send in another measurement, I feel a small but genuine pride. We amateurs are the neighborhood watch of the solar system, keeping an eye on the quiet drifters that share our star.

As a novelist, I can’t help imagining each of those dark wanderers as a character in a long, slow drama: ancient fragments of worlds-that-might-have-been, circling the Sun, waiting to play their next part in the story of life on Earth.

Mission 2: Electronically Assisted Astronomy — Seeing Through the Glow

Light pollution has stolen a sky that once belonged to everyone. Fifty years ago, I could step outside and see the Milky Way sprawl across the heavens. Now, from my observatory in southeastern Wisconsin, the naked eye sees only a washed-out gray. Even worse, as the decades pass, my own eyes have lost some of their youthful sharpness. The distant galaxies that once looked like faint pearls are harder to glimpse.

But I’m not ready to surrender the universe to city lights or aging retinas. Technology has given us a new way to see.

With electronically assisted astronomy (EAA), I no longer squint at a dim eyepiece. Instead, a sensitive camera gathers photons that have traveled across millions of years, then delivers them to a tablet screen. As the seconds tick by, the faint outlines of a nebula bloom into color, the arms of a galaxy twist into view.

I can even stay in the warmth of my house while the telescopes outside—guided by Wi-Fi and software—slew silently from one object to the next. I adjust focus and exposure by remote control. The images build in real time, not as an abstract dataset but as a living, deepening portrait of the universe. This is M13 in Hercules ... our observatory's "first light" image capture with the Askar 140 APO and ASI533MC Pro camera.

For a lifelong visual observer like me, it’s not a compromise. It’s a revelation. It lets me see the universe as it is—brightened by technology yet still raw, still alive—and it sparks the same curiosity that drives my science-fiction stories: what other eyes, on other worlds, might be watching back?

Mission 3: Astrophotography — Painting with Starlight

Astrophotography is the newest chapter in my long relationship with the night sky. While one telescope keeps its quiet vigil for asteroids, I often let another wander wherever my instincts nudge me—toward the faint glimmer of a distant galaxy, the loose scatter of a star cluster, or the soft glow of a nebula.

Each type of target demands a different approach. Galaxies like a narrow field of view; clusters and vast nebulae need a wide, generous frame. With the right filters, I can isolate the crimson signature of hydrogen-alpha, the ghostly blue of oxygen, or the golden filaments of sulfur—painting with the very elements that built the first stars.

The learning curve for processing these images is as steep as a cliff at lunar sunrise. I might spend hours—sometimes entire nights—collecting data, only to spend still more time stacking and refining it to reveal the faintest wisp of a spiral arm or the subtle glow of a stellar nursery.

Some nights I ask myself how I can sleep at all when the cosmos is whispering at the edge of the sensor. Will my first deep-sky portraits rival the masters I admire online? Almost certainly not.

But I’ve learned that wonder doesn’t wait for perfection. After five decades at the eyepiece, I know the sky well enough to find the treasures; what I’m learning now is how to let modern technology reveal them in all their fragile detail.

My Journey in Astronomy — A Lifelong Origin Story

The James Webb Space Telescope and the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory are rewriting textbooks every month. But I’ve always believed the most important telescope is the one you have in your own hands—because it doesn’t just collect light, it collects you: your attention, your wonder, your questions.

I was in seventh grade when I first turned a borrowed, hand-held telescope toward the Moon.

I wasn’t expecting much—just a brighter white disk. Instead, I saw mountains casting long shadows, sharp-edged craters, and dark maria that looked like ancient frozen seas. That first glimpse of another world pulled me in and never really let me go. I needed a telescope of my own.

The answer came from the past: my grandfather’s six-inch reflecting telescope, salvaged after a basement flood. I coaxed the mount back to life, had the mirrors re-silvered, and began to learn the constellations.

That same year I enrolled in my first astronomy class at the local junior college—and to my delight the class had a night-time observing lab. There I peered through state-of-the-art Celestron telescopes and learned that the sky isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a living, evolving wilderness.

By high school I was volunteering at the college observatory. The big 18-inch reflector dominated the dome like a silent, waiting creature. I’d help run the planetarium shows, guide visitors at public observing nights, and when everyone else went home, the staff often left me in charge. I’d shut down the dome myself, long after midnight, having spent hours alone with that giant instrument and the turning heavens. It felt like I was on the night watch of a ship bound for the stars.

Years later I bought one of the first Celestron GPS 11-inch telescopes that rolled off the assembly line. The jump to automated “go-to” pointing felt like stepping into the future.

But the hunger to see deeper kept growing, and five years later I made the leap to a different kind of giant: a hand-built 18-inch Obsession Dobsonian, designed by Dave Kriege. It was pure mechanical elegance—a light bucket in the truest sense—and it showed me worlds I had only read about. And, who knows, you might even want to have your own observatory!

Those telescopes were more than gear. They were portals, each one opening a new chapter in the same long story: a boy who fell in love with the Moon’s craters grew into a man still chasing the light of distant suns—and began to imagine who, or what, might be waiting under other skies.

Some Telescope Basics — Tools for Your Own Voyage

The night sky is full of wonders, but to go from a casual glance to a true explorer, you need the right tools. Think of a telescope not as a gadget but as a portal. Choose the right one and it will show you a universe you didn’t know you could reach.

For beginners, there are three main kinds of telescopes:

- Reflectors use curved mirrors to gather and direct light.

- Refractors use precision-ground lenses.

- Catadioptrics—the “cats”—blend both, using mirrors plus a correcting plate at the front.

Each has its own personality. Reflectors give you the best bang for the buck and excel at faint, deep-sky objects like galaxies and nebulae. Refractors are usually more expensive per inch of aperture but show the purest, sharpest views of the Moon and planets. Cats are flexible—good at most things, great at none.

If you’re drawn to solar observing, you’ll need a telescope with dedicated filters—because even a glance at the Sun through an unfiltered telescope can blind you. Fortunately, several reputable makers sell safe, purpose-built solar scopes.

Aperture: The True Power

When people start out, they often obsess over magnification—“How many times closer will it bring Saturn?” The truth is, aperture—the diameter of the main lens or mirror—is the real power. The larger the aperture, the more light your telescope gathers, and the more detail you can see.

A good rule of thumb is that you can use about 30× magnification for every inch of aperture (about 1.3× per millimeter). A six-inch scope, for example, performs best up to around 180×.

On a steady night of excellent seeing, my Askar 140 mm refractor—about 5.5 inches—works beautifully around 165×. My 18-inch Obsession can push to about 540×. And my Takahashi FC-100DL, a superb 4-inch fluorite apochromatic refractor, often delivers crisp planetary detail at 200×—a rare feat for such a compact scope.

To calculate magnification for your own telescope: Divide the telescope’s focal length by the focal length of the eyepiece. For example, my Takahashi’s focal length is 900 mm. A 12 mm eyepiece yields 75×—a sweet spot for many objects.

Field of View and Mounts

Magnification tells you how close an object looks. Field of view (FOV) tells you how much sky you see at once. To find it, take the eyepiece’s apparent field (say 82° for a Nagler eyepiece) and divide by the magnification. In my Takahashi with a 12 mm eyepiece (75×), that’s 82 ÷ 75 ≈ 1.1°—about twice the width of the full Moon.

But even the best optics are useless without a stable foundation. The mount matters more than the tube. A good, solid mount lets you focus at high power without watching the image jitter away. Rule of thumb: choose a mount with at least twice the capacity of the telescope’s weight—because you will eventually add accessories such as heavier eyepieces, cameras, or guiding scopes.

Building a telescope.

My first telescope — that six-inch reflector — had been one of my grandfather’s treasures. Nearly forty years after I’d last seen that old “Dynascope RV-6,” I asked my extended family to start a search. Although it was in a state of shocking, total decay, one of my uncles offered to ship the scope’s main and secondary mirrors.

I added a curved spider array (it looks like a Venn diagram) to hold the secondary mirror. I added a new focuser and a set of eyepieces. The resurrected scope moves nicely and gives excellent lunar & planetary views and some nice glimpses of globular clusters, galaxies, and double stars.

The fact that my grandfather bought it in 1966 and I’m still using the same optical train in 2025 is a reminder: these aren’t just tools; they’re heirlooms—time machines in more ways than one.

Buying Used Gear

Amateur astronomers tend to treat their gear well, which makes the used-telescope market a surprisingly good place to shop. I especially trust the classified section at cloudynights.com.

Sometimes a rare opportunity appears. Years ago, Koji Matsumoto in Iida City, Japan, wrote online that he couldn’t see a meaningful difference between his prized Takahashi FC-100DL refractor and a far more expensive TSA-102S. When he offered the FC-100DL for sale, I pounced—ending up with the finest small refractors I’ve ever owned.

Buying New Gear

For new telescopes, I recommend these trusted dealers:

- Agena Astro

- Astronomics

- High Point Scientific

- and for solar gear, Lunt Solar Systems

Guidelines:

- Choose the largest aperture you can afford and comfortably handle.

- Stay sensible about add-ons—avoid “accessory fever.”

- For a solid, affordable start, an 8-inch Dobsonian is hard to beat. Many telescope dealers offer these, and I’d recommend this one.

- If portability is a plus, a 6-inch Celestron SCT is an excellent all-rounder. Here’s where you can find one.

And download a good sky-charting app such as SkySafari, which scales from beginner (free) to advanced. A telescope won’t literally be worth its weight in gold, but it will enrich your nights—and, like me, you may find yourself passing that curiosity on to the next generation.

The universe is VAST. How are you supposed to know what’s worth seeing?

I’ve spent hundreds of hours helping the public explore the heavens—and not long ago, I earned my Master Observer’s certificate through the Astronomical League. Their observing programs, quick-reference guides, and celestial goals for all skill levels have kept me excited about the night sky while sharpening my own skills.

As a bonus, all that time under the stars also fuels my imagination as a science fiction writer, helping me bring the cosmos to life on the page.

The Master Observer Award required completion of five core project areas (marked with an *). I then had to choose five more observing programs to qualify for the Master Observer Award. Being a total geek, I completed six:

• Messier Observing Program 110 observations & sketches

• Binocular Messier Program 110 observations & sketches

• Lunar Observing Program 100 observations & sketches

• Double Star Observing Program 100 observations & sketches

• Herschel 400 Observing Program 400 observations & sketches

• Hydrogen Alpha Program 80 observations & sketches

• Sun Spotters Program 25 observations & sketches

• Globular Cluster Program 50 observations & sketches

• Caldwell Program 76 observations & sketches

• Urban Program 100 observations & sketches

• Outreach Program 160 hours of evening & nighttime public-service

Such fun! And since I can’t cover everything here, another source of information about amateur astronomy is cloudynights.com.

Little to big, these are our observatory’s light-gathering instruments:

Perched under a canopy of stars, my observatory is where science and imagination meet. Equipped with the following telescopes, I track planets, distant galaxies, and the occasional unpredictable comet. Every night, the sky becomes a canvas for discovery—sometimes inspiring a plot twist, other times a character’s epiphany.

Beyond mere observation, this space is a laboratory for ideas. I test the limits of human curiosity and wonder, letting the universe shape stories that blend fact with fiction. From the dance of binary stars to the eerie glow of nebulae, each celestial spectacle sparks new worlds, new conflicts, new adventures. Why not look up, imagine, and let the cosmos rewrite the rules of reality?

1. William Optics ZenithStar 71 (ED), 20th Anniversary Edition

Aperture: 71 mm | Focal ratio: f/5.9 | Low CA Japanese Ohara glass in a precision lens cell

Compact, precise, and elegant, the ZS71ED is the perfect travel or eclipse scope. Its doublet ED optics deliver crisp, low-chromatic-aberration views, whether scanning the Moon, planets, or star fields. We pair it with an ASSF 80 solar filter for stunning white-light solar observations and photography—a tiny package with enormous potential.

2. William Optics Gran Turismo 81 APO (Gen IV)

Aperture: 81 mm | Focal length: 478 mm (383 mm with reducer) | Focal ratio: f/5.9 (f/4.72 with reducer)

This triplet APO is optical wizardry at its finest. One of the lenses uses FPL-53 glass, delivering razor-sharp, zero false-color images. Fully multicoated with STM coatings, the GT81 offers expansive, immersive views. A 15x, its field spans over five degrees—eleven full moons across! For imaging, the reducer brings the ASI533MC Pro to a 1.69° x 1.69° field with 2.03”/px resolution. Features like the camera angle rotator, Bahtinov mask cover, and electronically controlled focuser make observing and imaging effortless.

3. Takahashi FC100DL Apochromatic Refractor

Aperture: 100 mm | Focal length: 900 mm | Focal ratio: f/9

This classic 4-inch refractor offers breathtaking lunar and planetary views. One of the earliest production units, it shines with perfect sharpness even at 225x and higher magnification, still free of false color. A 31mm Nagler eyepiece reveals wide, immersive star fields at 29x, ideal for relaxed evening observations. For me, this is the “sit back and marvel” telescope—simple, pure, and endlessly inspiring.

4. Askar 140 APO Apochromatic Refractor

Aperture: 140 mm | Focal length: 980 mm (f/7) and 784 mm (f/5.6 with its 0.8x reducer)

Versatile and sharp, the Askar 140APO excels for both visual observing and imaging. Its 140 mm objective produces crisp, high-contrast views across the sky, from the Moon and planets to deep-sky clusters and nebulae. Add the reducer, pair it with the ASI533MC Pro, and it becomes a wide-field astrograph, capturing faint details with clean, edge-to-edge sharpness—perfect for ambitious imaging sessions. The pixel scale matches well to typical seeing conditions, offering both efficiency in capturing faint detail and control of noise in long exposures.

5. Celestron 11 (C11)

Aperture: 280 mm | Focal length: 2940 mm | Focal ratio: f/10.5 (f/6.6 with reducer)

This carbon-fiber powerhouse transformed my observing life. With the C11, globular clusters, planetary nebulae, and galaxies come alive. Its f/6.62 imaging setup yields a 0.35° square field—ideal for deep-sky precision work. Over decades of using manual scopes, this one cut search time dramatically. Paired with an AT80ED guide scope and AS533MC camera, its efficiency and versatility are unmatched. Depending on binning, we use several resolutions: Bin 2 = 0.84”/px,Bin 3 = 1.26"/px, Bin 4 = 1.67"/px. I built my first observatory around this telescope and logged — yes, as with drawings and notes — several thousand objects.

6. 18” Dave Kriege Obsession Dobsonian

Aperture: 457 mm | Focal length: 2056 mm | Focal ratio: f/4.5 | Limiting magnitude: 16.0

Enormous yet surprisingly manageable, this 18-inch reflector is a beast of light-gathering power. Its 254.5-square-inch mirror brings more than 80 times the light of a typical 50 mm finder into view. Magnifications range from 66x (1.24° FOV) to 514x (0.10° FOV) under perfect skies. We’ve upgraded this Obsession (#451) with premium coatings, encoders, Argo Navis digital setting circles, a dual-speed focuser, and dew control—making it a dream for deep-sky and planetary observing. For more information, see this article.

Even with the light of the Milky Way barely outgunning our local light pollution, planetary nebulae, globular clusters, and faint galaxies just seemed to want to JUMP into view! In one short session, I saw HII regions in the Andromeda Galaxy, color in the Ring Nebula, and several moons of both Uranus and Neptune! Although the M81 and M82 galaxies are familiar targets, nearby NGC 2976 and 3077 were easy catches! Were those dark lanes in M13? Was that Galaxy NGC 6207 right next door? The Orion Nebula looked like a blue-green, three-dimensional image from NASA.

In case you want one of your own, here’s a link to Obsession Telescopes. Dave Kriege makes these here in Wisconsin, and describes this model as having “Fantastic deep sky and planetary images. One look and you’ll re-learn what it means to be excited about astronomy.”

The Mounts:

1. Losmandy G11G

If telescopes are the eyes of an observatory, the G11G is its steady spine. This hand-tuned marvel of precision engineering holds everything I set on it with the confidence of a seasoned guide. Sleek, balanced, and immaculately crafted, it moves with a whisper, letting the Grand Turismo 81, Askar 140 APO, or the Celestron 11 glide across the heavens as if the night sky itself obeyed its will. Here's a link to Losmandy!

With a payload of up to 50 pounds for imaging and 65 for visual observing, I can attach almost anything in my collection. Its tracking is impeccable—±5 arcseconds uncorrected, ±2.5 with periodic error correction—and the Gemini II controller remembers over 42,000 objects, pointing with uncanny accuracy, sometimes almost like it anticipates where my curiosity wants to wander next. Wizards built in for polar alignment, model building, and error correction make even the most complex nights effortless. Pair it with an ASIAir+ and SkySafari, and the G11G becomes a silent partner in exploration, allowing me to roam the cosmos from my iPad as if I had hands in both worlds at once.

2. iOptron AZ-Mount Pro

Not every adventure demands the gravity of an equatorial mount. For those nights when speed, simplicity, and versatility matter, the iOptron AZ-Mount Pro is my steadfast companion. It doesn’t just carry a telescope; it carries the promise of spontaneous discovery. With its rock-solid Tri-Pier tripod and built-in GPS, it calibrates itself in seconds, instantly knowing where it is and where I want to look.

Its payload holds 33 pounds comfortably—and with a little balancing magic, I can attach another 10-pound scope on the other side. Over 212,000 objects live in its onboard database, and I’ve yet to find one it can’t point to. A built-in battery lets me wander the yard freely, untethered by cords. And wireless control via SkySafari and my iPad turns observing into a graceful dance rather than a technical chore. Rugged yet elegant, the AZ-Mount Pro transforms even a casual evening under the stars into a precise, effortless voyage.

The Cameras: Eyes on the Universe

1. ZWO ASI533MC Pro

Think of the 533MC Pro as the observatory’s sharp-eyed artist. Cooled and compact, it sees both faint nebulae and bright star clusters with remarkable clarity. Its 3.76 μm pixels and 3008 x 3008 array produce crisp, balanced images with almost no fuss—perfect for both deep-sky imaging and electronically assisted astronomy (EAA). Paired with the Askar 140APO, it frames galaxies and nebulae like a painter’s canvas, revealing detail without distraction.

Its 2-stage TEC cooling keeps thermal noise at bay, while the 14-bit analog-to-digital conversion and 20 fps capture make every photon count. Controlled through ASIAir+, the camera can focus automatically, plate solve, and even command the mount—transforming my iPad into a bridge between Earth and the stars.

2. ZWO ASI220MM-mini

The ASI220MM-mini is our stealthy guide, a monochrome scout with a sixth sense for faint stars. Its 4 μm pixels and sensitive Sony sensor lock onto guide stars effortlessly, keeping long exposures perfectly aligned. Though small, it doubles as a planetary and lunar explorer, revealing detail with four times the sensitivity of a same-sized color camera. High quantum efficiency and low-light performance make it indispensable for long nights when every photon matters.

3. Coming Soon: ZWO ASI2600MC Pro

The 2600MC Pro is the future of our imaging adventures—a wide-field visionary with a 26 MP APS-C sensor. As the 533MC Pro’s big sibling, it is cooled, clean, and amp-glow-free, but then adds expansive framing, deep well capacity, and even more dynamic range. With the Askar 140 refractor, it promises professional-grade images of sprawling nebulae, intricate galaxies, and expansive star fields—a camera built for both detail and grandeur.

So, Are You Ready to Jump into Backyard Astronomy?

The Big Dipper awaits. Star clusters. Galaxies. Nebulae. And don’t forget the Moon and planets—your first view of Saturn’s rings is unforgettable. Comets streak across the sky. The International Space Station glides overhead. Meteor showers paint the night. The northern lights dance in the darkness!

The night sky can also be a playground for ideas. EAA, astrophotography, and astrometry are my companions, letting my mind wander across the cosmos and back to the page. While I’m building research notes for Sapphire Sky and Urgent, I’m deep into Crimson Abyss, and Murdoch McRae is nearly finished narrating Orphans of Fire. Every photon from a distant cluster that lands on a sensor sparks a question: What does it mean to be aware of the universe at all?

That question drives my science-fiction. In Crimson Abyss, Daryle Chantree and Nikola Tesla encounter the Dhyda—an alien species whose elders can transfer their entire consciousness into a younger body. Such beings challenge everything we know about identity: Is consciousness bound to a single brain, or can it be carried like a song into a new instrument?

The observatory provides the data. The stories provide the experiment. Both, in their own way, are about seeing more clearly.

An Invitation

If you’ve ever tilted your head at night and felt a flicker of wonder, you already have the most important qualification for astronomy. Start small: binoculars or a modest telescope. Download a sky app like SkySafari. Learn a few constellations. Watch a meteor shower.

If the spark catches, you can go further: help monitor asteroids, track comets, or capture live images of distant galaxies. You don’t need a PhD—just curiosity and persistence.

I built the Wolf Moon Observatory to chase stars and wandering specks of rock across the sky—and to spark the questions that drive my stories. So, please visit my Amazon author page and explore my books, guides, and previews.

The sky is more than a laboratory. It’s a mirror, reflecting both the universe above and the questions we carry inside.

Please visit my Amazon Author page for updates as I write my 14th novel! In Crimson Abyss, I’m taking Daryle Chantree’s sixth time-travel mission—once lived as fact—and reshaping it into fiction. The line between history and imagination has never been thinner! Please join my mailing list to follow the adventure as it unfolds!

P.S. This article has been endorsed by ZEKE: